The European Commission wants to simplify medical device regulations.

Everyone is talking about reduced burden, but will you actually translate less?

The short answer: probably not. In fact, you may end up translating more.

While the proposal introduces potential language flexibility for some professional-use devices, it simultaneously expands the scope of regulated digital content, all of which carries the same translation obligations as paper equivalents. Simplification at the regulatory level does not automatically mean simplification at the translation level.

Here’s what medical device manufacturers, regulatory teams, and localization managers need to understand about the December 2025 EU MDR/IVDR Regulation revision proposal and its real impact on translation strategy.

Why the EU Is Proposing Changes to MDR and IVDR

Since the EU MDR regulation took effect in May 2021 and the In Vitro Diagnostic Regulation (IVDR) followed in May 2022, the system has struggled under its own weight. The framework raised expectations around safety, clinical evidence, and transparency, but the infrastructure needed to implement the EU MDR regulation has not expanded at the same pace.

Only around 51 MDR and 19 IVDR notified bodies have been designated, far too few for the estimated 23,000 certificates that need to be issued. The result has been certification bottlenecks, slower market access, withdrawal of critical devices, and unsustainable pressure on manufacturers, especially SMEs. Something had to give.

The European Parliament called on the Commission to act in October 2024. By December 2025, the Commission delivered. Language requirements entered the conversation because they are one of the many compliance areas where proportionality and burden reduction could apply, particularly for devices used exclusively by trained professionals.

The December 2025 Proposal: What Makes It Different

Published on 16 December 2025 as COM(2025) 1023, this is the first major structural revision of MDR and IVDR since their implementation. The proposal is open for feedback until March 2026, and strong political momentum, including Parliament’s October 2024 resolution calling for urgent reforms and looming transition deadlines suggests it is likely to move forward relatively quickly through the ordinary legislative procedure.

Unlike previous transitional extensions that simply pushed deadlines, this proposal tackles root causes: disproportionate requirements, unpredictable certification timelines, divergent national practices, and barriers to digitalization.

For translation professionals and regulatory affairs teams, the implications run deeper than they first appear. The headline is “simplification,” but for language and localization, the reality is more nuanced.

The Three-Tier Future: Strategic Scenarios for Translation Planning

To plan effectively, manufacturers should think about translation requirements in terms of scenarios rather than blanket rules. Here is how the landscape may evolve across different device categories:

1: Professional-only devices (Class IIa/IIb)

Today, most markets require full translation. In the near term (2026–2027), a small number of Member States may introduce flexibility for professional-use devices, potentially accepting English or another EU language. By 2028–2030, this flexibility could expand gradually to more countries, though adoption will remain uneven.

2: Patient-facing devices (all classes)

No meaningful change is expected. Translation into national languages will remain mandatory across the EU for any device that reaches patients or lay users.

3: Software and digital health devices

The translation scope is closely tied to the intended user. As digital content grows, including eIFUs, online portals, and in-app instructions, the volume of translatable content is increasing, not decreasing. This trend will continue.

4: High-risk implantable devices

SSCP scope may be reduced under the proposal, but the language obligations for information supplied with the device will remain firmly in place.

The strategic implication is clear: build flexibility into your contracts, workflows, and vendor relationships now so you can respond quickly as country-level rules shift.

How Translation Requirements Work Today Under MDR and IVDR

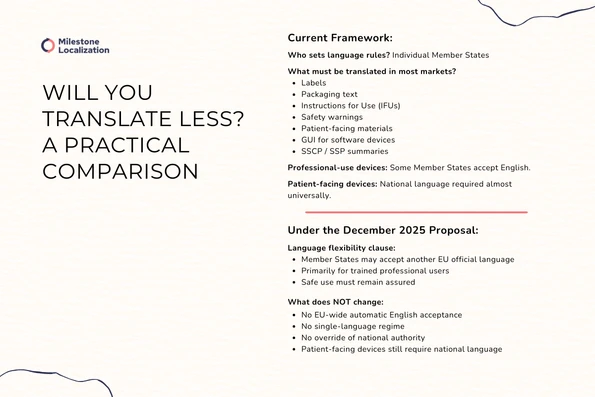

Translation obligations under the current EU MDR regulation are not set at the EU level in a uniform way. Instead, Article 10(11) of the EU MDR regulation and Article 10(10) of the IVDR require manufacturers to provide information in the languages accepted by the Member States where the device will be marketed. Each Member State decides its own rules.

In practice, this means most manufacturers must translate the following for every target market: labels, packaging text, Instructions for Use (IFUs), safety-critical warnings, and patient-facing information. For software devices, the graphical user interface (GUI) is also considered part of the IFU and subject to the same language obligations.

There is an important distinction between devices intended for lay users and those for professional use. Several Member States already accept English for professional-use devices, while patient-facing devices almost universally require translation into the national language. The Summary of Safety and Clinical Performance (SSCP) under the MDR, and the Summary of Safety and Performance (SSP) under the IVDR, carry their own language obligations as well.

Also Read: MDD vs MDR: Key Differences in Translation and Language Requirements

The Proposed Language-Flexibility Clause, Explained Simply

One of the more quietly significant elements of the proposal is a provision encouraging Member States to consider whether information supplied by the manufacturer could be accepted in “another official EU language”, rather than strictly the national language, where safe use is not compromised.

This is not a mandate. It is an encouragement, directed at Member States, and it applies primarily to situations where the end user is a trained professional who can reasonably be expected to work in a language other than their mother tongue. The key factors are user training, expertise, and whether safe use can be maintained.

What the proposal does not introduce is equally important: there is no automatic acceptance of English across the EU, no single-language regime, and no override of national authority. Each Member State retains the right to determine its own language requirements. The proposal simply opens the door for some to relax them in specific, low-risk scenarios.

Notified Bodies and Submission Language: A Quiet but Meaningful Shift

Beyond patient-facing documentation, the proposal also touches on the language of regulatory submissions. Currently, notified bodies often require documentation, clinical evaluation reports, technical files, and quality management system documentation in specific languages, which can vary from one body to another.

The proposal suggests that notified bodies may accept documentation in any EU official language agreed upon with the manufacturer. This could reduce the translation burden for regulatory submissions, particularly for manufacturers working with multiple notified bodies across different Member States.

However, this flexibility will only deliver value if manufacturers engage early. Confirming acceptable submission languages with your notified body before starting the conformity assessment process becomes a critical planning step.

Digitalization and Its Effect on Translation Scope

The proposal strongly pushes toward digitalization: electronic IFUs for a broader range of devices, digital labelling, online sales information requirements, and electronic submissions via EUDAMED and other platforms.

From a translation perspective, this expansion of digital content does not reduce scope — it increases it. Electronic IFUs must meet the same language requirements as paper versions. Online product information and sales listings are regulated content, with eIFUs required to be available on the manufacturer’s website in an official language of the Union determined by the Member State where the device is made available. Digital portals and platforms must be accessible in applicable languages.

For software-based medical devices regulated under the EU MDR regulation, the graphical user interface may qualify as an IFU when no separate instructions are provided, as established under MDR Annex I, Chapter III, and confirmed in the Commission’s MDR language requirements tables. As more devices incorporate digital interfaces, the volume of translatable content grows proportionally.

Also Read: EU CTR 536/2014: Translation Requirements

Looking for Medical Device Translation services?

What This Means for Medical Device Translation Strategy

The direction of the proposal points away from blanket, one-size-fits-all translation rules and toward a more fragmented, country-by-country landscape. This creates both opportunities and risks.

On the opportunity side, manufacturers of professional-use devices may be able to reduce translation into certain languages for certain markets, a genuine cost saving if managed well. But this flexibility only works if it is governed deliberately, with clear internal policies on which devices qualify, in which markets, and with proper documentation to demonstrate compliance during audits.

On the risk side, inconsistent language practices across channels, markets, and device types can create compliance gaps that are harder to detect and more expensive to fix.

Segmenting your product portfolio by intended user, professional versus lay, is now essential. Devices reaching patients will continue to require full translation. Devices used only by trained professionals may not. Knowing which is which, product by product, is the starting point for any updated translation strategy.

What Manufacturers Should Do Now

The proposal has not yet been adopted, and the final text may differ from the December 2025 version after Parliament and Council review. But waiting for finalization is not a sound strategy. The manufacturers who move early will have the flexibility to adapt; those who wait will be forced to react.

Here are the steps that forward-thinking manufacturers should take now:

1: Track national language rules actively

The Commission and Member States publish language requirement tables for both MDR and IVDR. Monitor these for changes, especially in markets where you sell professional-use devices.

2: Segment your product portfolio

Map each product against its intended user, professional versus lay, and the risk class. This segmentation will determine which products might benefit from emerging language flexibility and which will not.

3: Align regulatory, quality, and localization teams early

Translation decisions should not be made in isolation. Regulatory affairs understands the legal requirements, quality assurance owns the QMS processes, and the localization team manages execution.

4: Treat digital content as regulated from day one

Whether it’s an eIFU, a web portal, an app interface, or an online sales listing, digital content carries the same language obligations as paper. Build this assumption into content creation workflows.

5: Engage your notified body on submission language

If the proposal’s flexibility around submission language is adopted, early agreement on acceptable documentation languages could save significant time and cost during conformity assessment.

Flexibility Does Not Mean Less Translation

The word “simplification” creates an expectation of reduced effort. In the context of MDR/IVDR language requirements, that expectation needs to be tempered.

Translation remains a core compliance requirement for placing medical devices on the EU market. The proposed revision does not change that fundamental obligation. What it does change is the strategic complexity of managing it.

Companies that start segmenting their portfolios, mapping national rules, and aligning their internal teams now will be positioned to move quickly when the rules shift. Those who wait will face last-minute rework, inconsistent compliance, and avoidable costs.

Regulation is evolving. Your translation strategy should evolve with it, not after it.

Stay informed on EU MDR regulation and IVDR developments by following regulatory updates from the European Commission and your notified body. For questions about how these changes affect your translation and localization strategy, consult with qualified regulatory and language service professionals.

Are You Looking for a Reliable Partner for Your Regulatory Translations?

FAQs

What is the latest update to the EU MDR regulation in 2025?

The latest 2025 revision proposal to the EU MDR regulation (COM(2025) 1023) aims to simplify certain requirements that have created bottlenecks since implementation. The proposal addresses certification capacity, proportionality of obligations, digitalization, and limited language flexibility for professional-use devices. Core safety and transparency requirements remain unchanged.

Does the EU MDR regulation require medical device translation into all EU languages?

No. The EU MDR regulation requires manufacturers to provide information in the languages accepted by each Member State where the device is marketed. Each country sets its own language rules. In practice, this means most patient-facing devices require translation into the national language of each target market.

Will the 2025 proposal reduce translation requirements?

For most devices, no. Patient-facing products will continue to require full translation. Some Member States may allow greater flexibility for professional-only devices, but this is not automatic and will depend on national implementation. Digital content remains subject to the same language obligations as printed materials.

How should manufacturers adapt their translation strategy under the evolving EU MDR and IVDR regulation?

Manufacturers should segment products by intended user, track national language rules continuously, align regulatory and localization teams early, and treat digital content as regulated from the start. Flexibility may emerge for some professional-use devices, but patient-facing translation remains a core compliance requirement.

How early should manufacturers start translation planning for the May 2026 deadline?

Manufacturers should start as early as possible, since regulatory translation involves review cycles and quality controls. A realistic plan is:

- 2–4 weeks for single-language IFU/label translation

- 6–12 weeks for 10+ EU languages (including review cycles)

- 3–6 months for larger portfolios, SSCPs, and technical documentation with SME validation

Starting early also allows you to build terminology and translation memory for faster future updates.